Hill Agency: PURITY/decay review

- 0 Comments

Beautiful Indigenous detective mystery diminished by bugs and spotty implementation

Achimostawinan Games (translated to “Tell us a story” in Cree) is an Indigenous-owned game studio and hopefully one of many more to come. Hill Agency: PURITY/decay is their first game, a futuristic detective noir mystery in which the colonizers have mostly left Earth and the few major cities remaining are run by Indigenous people. As an illustration of Néhinaw culture and what a future Land Back world could look like, Hill Agency is a beautiful success. Unfortunately, as an adventure game it’s still quite rough around the edges, even with all the effort the developers have put into smoothing them out since launch.

You play as Meeygen Hill, a Néhinaw private investigator in the year 2762 who’s been low on work, a fact that your aunt (who lives across the hall) won’t stop razzing you about. Your first case is a simple mystery to track down your niece’s missing ElectroDog 2.0. You’ll search the neighborhood for leads and interview family, friends, and locals to not only find the toy, but also the culprit responsible for its disappearance. After successfully solving this tutorial case, you are visited by Mary, an elite (someone from the upper class who normally isn’t seen among the natives) from nearby Risen City (literally; it’s in the air), who is willing to pay big money to help solve the murder of her sister after the police write off her death as an overdose. This homicide case will take up the rest of the game.

Investigation is fairly straightforward, as you’ll talk to anyone who will listen, scour for clues when prompted, and try to connect evidence to a suspect. Frustratingly, the mechanics employed for each of these tasks are overly simplified and often buggy. Interrogating witnesses and potential suspects should be the bread and butter of any detective game, occasionally tense and with careful attention to detail to be effective. Here it simply entails exhausting conversation trees with no way to make a mistake or change the course of the inquiry. Some characters that helped you during the ElectroDog 2.0 investigation are still present during the murder case, yet you will ask them about the toy as if that case hasn’t already been solved. In one instance, I repeated a conversation with a character who wasn’t even in the room anymore.

Finding clues has similar issues. There are not many to uncover, and the game generally prompts you to search for them when you enter rooms that contain them. Clicking every hotspot is all that’s needed, and you will only keep items that are relevant, leaving no red herrings that could give the investigation any challenge. Half of the clues won’t even disappear from rooms after they’ve made it to your inventory. You can continue to “find” them and will have the same internal dialogue as if this is all new to you.

Connecting the evidence poses many of the same problems. You have an evidence board in your office where you can place clues and literally draw links between them. However, this is simply a sandbox you can use to visualize aspects of the case, dragging and dropping avatars of suspects and evidence onto a board. I found it easier to simply use pen and paper, especially since I could never get the drawing function to work.

While in your office, at any time you can talk to Mary – who is curiously always waiting for you both in this room and many others, even if she was last seen walking behind you – and make an accusation. Doing so involves the same drag and drop of a suspect and evidence (on a separate screen from the evidence board) and Mary will let you know if she agrees. If she doesn’t, you will capitulate and try again. Not only does this eliminate any gravity from the accusation, it also serves to undermine you as a detective, since you can only follow your gut instinct when the layperson who hired you agrees. But with no potential misdirections to worry about, there is really only one logical choice of whom to accuse anyhow. Once you make the correct accusation, you and Mary will then confront the perpetrator.

I could forgive some of this overzealous streamlining if the story were more engrossing and tightly written. The exploration of Néhinaw culture and how it might adapt to this future Land Back scenario is compelling, and the characters for the most part generally have distinct personalities, with motivations that don’t always align with Hill’s. However, in addition to some distracting typos, there is a lot of dead time and some logical inconsistencies that get in the way of the narrative.

The plot, involving a tangled web of corruption, does progress at a nice pace, gradually building to something more complex than Hill’s initial investigation. However, each big reveal feels rushed and poorly implemented. In one office building, you cannot open the break room fridge because it is locked. But shortly thereafter you enter a horrifying room that is neither locked nor guarded, with computer controls easily accessible. At another time, you learn that an endearing informant has been murdered, but the music and conversation don’t match the weight of what you’ve just discovered. To top it off, the grand confrontation at the conclusion of the game ends with a whimper, as you simply scroll through conversation trees and wind up a passive observer to the resolution of the case. So even at the climactic point in the story, the modicum of detective work you’ve engaged in to reach that point feels largely unrewarded.

Moving Hill around is done with tank controls (using the keyboard or a gamepad) reminiscent of Grim Fandango. This choice is puzzling given that none of the cinematic camera cuts benefit from using this system. While it’s not terribly frustrating, a more standard control scheme would have made for a smoother experience. You cannot even enter locations just by approaching them (even ones without doors), but rather must press a button to indicate you want to go in.

Worse than the controls is how painfully long it takes to get anywhere. There are a few different city blocks Hill must traverse repeatedly, with little to do and no option to run or quick travel from one end to the other. As it takes approximately 50 seconds to traverse a block, this becomes a painful slog, especially when you’re feeling stuck and just wandering around.

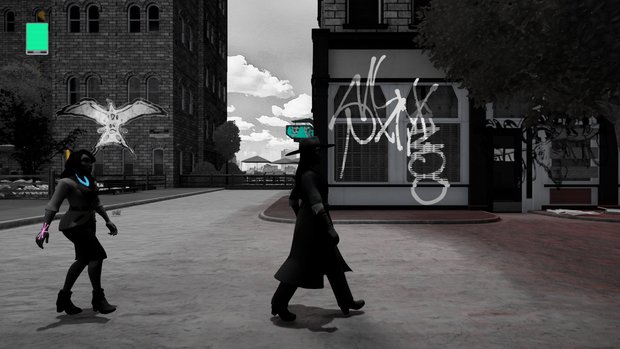

At least the locations are a treat to explore, as I was legit wowed by the graphics. The designers wonderfully merge a noir aesthetic with Néhinaw philosophy. The 3D presentation is mostly rendered in black and white, interlaced with neon hues from signs and computer terminals. The respect for nature is ever-present, with undisturbed parkland and plants growing everywhere (including the sidewalks) and hanging off of every balcony. Apartments have been repurposed as multigenerational homes. All of the clothes are handmade. Remnants of the dominant culture have not been disposed of, but rather adapted to meet their needs. This is in stark contrast to Risen City, whose soaring carbon footprint is punctuated with intrusive advertisements and excessive vanity. Most locations have a visually arresting element and great detail is paid to every scene, whether it can be interacted with or not.

There are no strangers in this town, as everyone is family to Hill, creating a bubble of safety rarely afforded to real-world Indigenous people in contemporary cities where they are the minority. Néhinaw language is also frequently used by characters, and while understanding it isn’t integral to moving through the game, I found myself researching the language to better immerse myself. It’s too bad there’s no chance to hear it voiced, as all dialogue is in text form. The background music is your classic noir-style jazz; while it’s a very pleasant listen, it is quite repetitive and there is a low variety of tracks to keep things fresh.

Final Verdict

Ultimately, your enjoyment of Hill Agency will likely rest on how much pleasure you take from just experiencing its distinctive world and characters, because as a game it looks uniquely beautiful but in its current state is still riddled with bugs and requires very little detective work to advance the story. Only a few hours is needed to see all there is to see, and a significant portion of that is spent walking back and forth. Thus I am left unable to recommend the game with any real enthusiasm. That said, for those interested in other cultures, Hill Agency: PURITY/decay is a rare opportunity to partake in an authentic Indigenous story. On a personal level, it perhaps didn’t hold the same resonance for me as a cultural outsider as it would to fellow Indigenous peoples, but I greatly appreciated this authentic look into Cree culture, albeit in a fictional future context. I may not have had much fun playing, but I was inspired to spend a good deal of time researching Néhinaw culture afterwards. There’s plenty of room for improvement, but I am optimistic for the future of Indigenous-made titles and look forward to any future releases by Achimostawinan Games.

Hot take

Hill Agency is a stylistically gorgeous game and a refreshing futuristic representation of Indigenous people, but otherwise this detective noir game is too hampered by bugs and a lack of real investigative work to make the experience worthwhile.

Pros

- Authentic representation of Néhinaw culture

- Stunning artistic style combining classic noir and Indigenous aesthetics

Cons

- Detective work is exceedingly simple with no way to make a mistake

- Tank controls are cumbersome and add little to the cinematic experience

- A good portion of the game is walking slowly from one location to another

- Bugs still permeate every aspect of play

Beau played Hill Agency: PURITY/decay on PC using a review code provided by the game's publisher.

0 Comments

Want to join the discussion? Leave a comment as guest, sign in or register in our forums.

Leave a comment