Centum review

- 0 Comments

Too much meandering, meaningless obtuseness drops an otherwise compelling presentation far below one hundred percent

There’s an old saying, variously attributed to everyone from Confucius to Charles Darwin, which describes a philosopher as “a blind man in a dark room searching for a black cat that isn’t there.” Centum, by Estonian studio Hack the Publisher, offers players the rare chance to learn what that feels like from the inside. You have an objective, but not the specifics; you’ll be asked to take action, but rarely told why. The panoply of weird characters you meet do a lot of talking, but whether they’re actually communicating anything is an open question. It might just be that they say everything except what they mean and expect you to figure it out by elimination.

And yet there’s a compelling kernel of something at Centum’s core, a sense that maybe you could fit everything together, if only the pile of unused puzzle pieces would stop growing at such an alarming rate. It’s the notion that it might all come together into something comprehensible—that the head-scratching and bemused eye-blinking will have been not only justified, but necessary—that’s liable to keep you clicking through Centum’s increasingly surreal scenarios. The longer you play, though, the harder it gets to ignore the disconnect between that impression of immanent potential and the lackluster reality, and you’re likely to come away feeling you’ve taken part in an intriguing but mostly fruitless experiment.

Centum begins at a computer console, as your nameless, faceless protagonist prepares to log into the system that interfaces with an advanced AI called BeMK. It’s obvious that your character was instrumental in BeMK’s development, but that’s where the concrete detail stops. All you know for sure is what you’re doing in the moment, and that you’re utterly alone—-save for BeMK “himself,” of course. Why BeMK (or “Beemkie,” as his programmers affectionately called him) was created, and to serve what purpose, isn’t immediately clear; what is clear is that the project went wrong somewhere and led to worldwide catastrophe. A note on your desktop urges you to find a young man called Marmoset, who was also critical to the BeMK project before his apparent disappearance. Only he knows for sure what’s happened, and finding him might help to mitigate some of the damage.

Another desktop note prompts you to take your first step: clicking the icon that launches the main BeMK terminal and opens a mysterious, one-room adventure game dubbed _100.bat. Why does your search for Marmoset start here? Having played the whole game, I still couldn’t tell you; it’s the first of many, many instances where Centum opts to toss you in the deep end before you’ve learned what “water” is. You can either hold your breath and try to paddle, or flail around and hope for a life preserver.

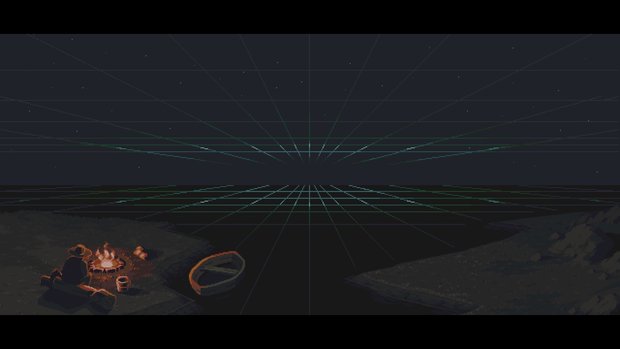

_100.bat, the first-person, pixel-art-styled game-within-the-game, is set in a stone prison cell. Per the desktop note that guided you there, you have three in-game days to escape. There’s a bed, a window, a table, a door, and no additional instruction. You’re free to click around; hotspots flash white under your cursor, and a single click activates them. Picking something up places it at the top of the screen in your inventory, but you won’t take it out to use directly; when the right situation arises, a dialogue menu will prompt you to do what you need with it.

Most of the gameplay occurs via these menus, similar to a visual novel. Sometimes this means actual dialogue—you’re far from alone in this cell, it turns out—but other times you’ll be given a handful of actions to choose from. Clicking a rat trap in the middle of the floor, for instance, prompts you either to ignore it or set it up. Do the latter, and you can then choose to move it, leave it be, or stick your hand in it. (Hey, it’s your hand—do what you want with it!) There are no stock “that doesn’t work” responses: if the game says you can try something, you can, and the consequences will affect how the scenario unfolds.

Centum alternates between sequences set at your character’s computer desktop and additional runs inside _100.bat, the latter changing drastically with each completed three-day cycle. (An in-game “day” will pass when you choose to sleep. You’re free to press Escape to go back to the simulated desktop to consult your character’s notes or access Centum’s main menu; there’s no penalty for leaving and returning.) At a certain point you’ll come back only to find that the prison cell is gone, replaced by a studio apartment belonging to a lonely programmer, where he works developing—what else?—a program called BeMK. Complete that cycle and you’re transported to an enclosed playground, where you’ll join four characters called “the Rats” as they navigate the machinations of a secretive and tyrannical government.

While the player characters in each new _100.bat iteration all have different reasons they can’t leave—the programmer is trying to finish his work, for example, while the Rats have “business” on the playground—escape remains the primary goal. Other puzzles mostly center on observing and repeating patterns, as in a tic-tac-toe game with an unseen opponent, but choice and consequences are the game’s main focus. Whatever you choose in a given situation determines what happens next, but (with one glaring exception) none is more “right” than another. You’ll also spend time speaking with the uncanny beings who materialize in each setting, who hope to bend your ear and persuade you to see things their way. It’s up to you to figure out if you can trust them, and what to do about it if you can’t.

Realized in ultra-detailed close-ups, these creatures might have been plucked directly from a child’s nightmares: a human-headed rodent with bulging, vacant eyes and far too many teeth; a slack-jawed shadow-ghoul, decomposing as you watch; a man who’s “fixed” the problem of his absent face with what one hopes is dripping red paint. Even overtly humanoid characters have unsettling, hyper-exaggerated features that leave them looking like storybook goblins. As time passes, the environment in _100.bat begins to warp and degrade to match: walls bleed; furniture sprouts organs; familiar sights become deranged, funhouse-mirror parodies of themselves.

The cumulative effect of these recurring horrors, witnessed as you return again and again to a setting that changes but stays somehow the same, is of being trapped in a malevolent dream. You may wake now and then to your character’s desktop, but no matter what, you’ll always find your way back. Even if you could escape that cycle, you’d still be haunted by disturbing memories of your character’s former life that appear now and then in monochrome cutscenes animated like crude crayon flipbooks. The atmosphere is one of desperate, oppressive isolation without hope of relief; the haunting, minimalist synth soundtrack renders this almost palpable with squealing, theremin-esque pieces that evoke lonesome winds whistling through abandoned structures.

The desktop provides a brief respite from BeMK’s conjured terrors, allowing you to read your character’s email and access bookmarked websites; both provide clues to the larger narrative. Certain emails will prompt you to send a reply, offering you several topics to choose from before your character composes the message. The desktop also contains a handful of simple minigames that pop up at certain points in the story—a shooting gallery, a barebones driving sim, a tank combat game, a Chip’s Challenge-esque maze—all of which control with either the mouse, the keyboard, or both. (The game never tells you which, though, so you’ll have to figure it out by trial and error.) Like the casual games they mimic, these are quick, uncomplicated, and encourage a quick restart if you lose. And still, as you busy yourself with these seemingly innocent tasks, the sense of creeping wrongness grows: visual glitches that seem somehow purposeful; small slips in BeMK’s mask of affability. There’s something you’re not being told.

All this is effectively eerie and atmospheric, but Centum stumbles and ultimately falls in trying to translate those feelings to words. Both the narration and unvoiced dialogue tend toward overwriting and vague, excessively flowery language, so that no matter how much you read it’s hard to feel like you’ve learned anything. Most conversations consist of meandering, circular bull sessions on philosophy between your character and whichever leering id-demon happens to be present. The narrator rambles at length with no clear point, as in this passage concerning the sound of a strange object:

“The aelle sings a hauntingly beautiful tune. Her voice is high-pitched and dense, enveloping you like a lukewarm bath of muddy water that helps scrap [sic] off the biggest chunks of dirt yet does not leave you sparkling clean. This song is unpleasant at best, although still restorative. A patch of dirty snow, a morning hungover under the low-hanging clouds, a futile hope. The blue sky cuts through like a razor. The key note leads to catatonia subtly yet firmly.”

For all the elaborate description there, the narrator hardly seems to know what they’re trying to say. What does it mean for the tune to be both “hauntingly beautiful” and “unpleasant at best?” Why is the aelle—an inanimate, Rubik’s-like cube that isn’t otherwise personified—referred to as “her”? What “restorative” property should a hangover evoke, or dirty snow, and if the song induces the listener to catatonia—the inability to perceive or react to stimulus—then why this cascade of sense-descriptions? In short, does any of this mean anything, or does it just sound like it should?

Despite gesturing over and over again toward a hidden trove of secrets buried just beneath its surface, the feeling gets stronger as one plays that there’s less to Centum than meets the eye. What seem at first like mysteries turn out to be dead ends, as with the coded messages that sometimes pop up in dialogue and which you can decrypt using a program on the desktop. The process is enticing, but the ensuing “revelations” usually just restate what was clear from context, or what you already knew. The same is true of its characters’ extensive soliloquizing over philosophical quandaries. For as much of the game’s five hours as they spend repeating themselves and alluding to grand, obscure truths, it’s hard to glean much meaning from what they actually say. It starts to seem like the characters, and Centum more broadly, are just talking to hear themselves talk.

Take the desktop minigames as an example. There are vague hints that they connect to Marmoset in some way, but that nebulous “maybe” is all the context you’ll get. Perhaps playing them is supposed to put you further into your character’s mindset, but if so, why make the experience functionally identical to what it would be in the real world, i.e. mildly diverting and mostly forgettable? And yet you have to play them to progress the story, with the game even relenting and granting an “easy mode” so you can finish the driving sim more quickly if you crash a few times. (And again, since you must figure the controls out yourself, you probably will.) So far as I can tell, though, only the maze has any real narrative significance.

All of which raises the question that kept cropping up as I played: what is the point of all this? What about this story suits or justifies these design choices? Why, for instance, does the game spend so much time establishing that _100.bat functions as a sort of personality test for BeMK’s users, analyzing their choices and labeling them a “warrior,” “prophet,” “artist,” or “murderer,” only to never define or imbue those archetypes with any meaning? Why those categories, and not any of a thousand others? Why, if they’re so important, will the game shrug its shoulders at the end and proclaim you “none of the above” if your behavior doesn’t map neatly into one quadrant?

And the most baffling why of all: why does a certain choice within _100.bat lead to a dead end that locks you out of the rest of the game, and why, why, why does the game then fail to tell you that’s what’s happened? I clicked around aimlessly for quite some time, hoping to trigger whatever came next, before throwing up my hands and turning to the internet, only to learn that I’d blown it without knowing. While the game has an autosave system, meaning you can return to a point before the offending decision, choosing to reload is contingent on realizing you’ve been softlocked in the first place. Despite belonging to a genre where uncertainty about what to do next is often a feature and not a bug, there’s nothing here to tell a player they’ve failed.

If this was just a bug or accidental oversight, it would at least be understandable, but the developers have confirmed in response to a question on Centum’s Steam forum that the softlock is “intended game behavior.” Having experienced the “behavior” in action, all I can say is that whatever it’s meant to communicate about the game, the story, or the vast tapestry of human experience…it doesn’t. It’s not clever, interesting, or even legible: not as a design decision, not as a narrative choice, not even as a bit of developer sleight of hand. Instead it’s obnoxious, pure and simple, and it’s baffling that it made it into the final release.

Final Verdict

Centum is aesthetically compelling, with imagery that haunts like a deathbed hallucination and an oppressive, doom-laden atmosphere that grabs you by the hindbrain and doesn’t let go. The problem is that its ambitions extend far beyond that, and it flounders in trying to realize them. The mechanics and writing seem confused and aimless, and the game struggles to make its design choices feel relevant or justified in context. It confuses when it means to mystify; frustrates when it means to entice; rambles when it means to provoke thought. There’s some promise here, to be sure, but Centum doesn’t just depict an intractable struggle with a well-intentioned but flawed computer program; unfortunately, it also provides one.

Hot take

Centum is full of memorably horrific imagery and atmosphere, but enjoying them means putting up with uneven writing, poor design choices, and a truckload of obscurity for obscurity’s sake.

Pros

- Wonderfully disturbing scenery, character and creature design

- Memorable atmosphere of hopelessness and isolation

- Novel game-within-a-game presentation with choice-based branching narrative

Cons

- Meandering, overwritten script takes a long time to say very little

- Many features and mechanics without much connection to the story

- Gestures toward “mysteries” that ultimately lack substance

- Horribly misguided choice to allow an intentional softlock

Will played his own copy of Centum on PC.

0 Comments

Want to join the discussion? Leave a comment as guest, sign in or register in our forums.

Leave a comment