Once a Tale review

- 0 Comments

Twice the pleasure in this modern fairy tale interpretation presented in lovely hand-crafted, stop-motion animation

The fairy tales and fables we knew as children have an incredible power to loom in our imaginations, providing us with sustenance well into adulthood. In a Western context, figures such as Hansel and Gretel, Snow White, and the Three Little Pigs offer a comforting familiarity, while the witches and wolves that act as their antagonists serve as gentle metaphors for the forces of evil at work in our real world. Carcajou Games’ Once a Tale takes various characters from these stories and places them into a unique narrative captured in striking stop-motion animation with hand-crafted models and sets. While it does have its rougher aspects—and a fixed camera that creates some awkwardness—it also boasts solid puzzle-driven gameplay (with a dash of stealth), gorgeous sights and sounds throughout a beautiful world to explore, and a brilliant finale.

You play as Hansel and Gretel, at times switching between them over the course of your journey. In this incarnation of their story, the pair are the children of a poor woodcutter and his wife. Following a countrywide famine, the children’s parents abandon them in the woods. Narrowly evading an encounter with a large, terrifying wolf, the two wander through the forest until they stumble across a straw farm. The proprietor is one Hayward S. Pigue, the youngest of the Three Little Pigs. He warns Hansel and Gretel of his past experiences with the wolf, who blew down his house and set fire to what was left of his property. The wolf has also terrorized a young woman named Anne, who wishes to build a shelter in the forest that will offer refuge from the wolf’s villainy.

After assisting Mr. Pigue in collecting bales of straw, you will set about performing various tasks to aid in the construction of Anne’s shelter. Accomplishing this goal will require you to trek through several locations throughout the forest. Hansel and Gretel explore an underground maze, sneak past the wolf and other enemies, and search the recesses of an old mine. Along the way, you will have interactions with a number of familiar faces, including Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, Tom Thumb, the Pied Piper, and, of course, the Big Bad Wolf. While its story is simple, Once a Tale is not particularly short—between exploration, conversation and figuring out solutions to puzzles, my full playthrough took around eight hours.

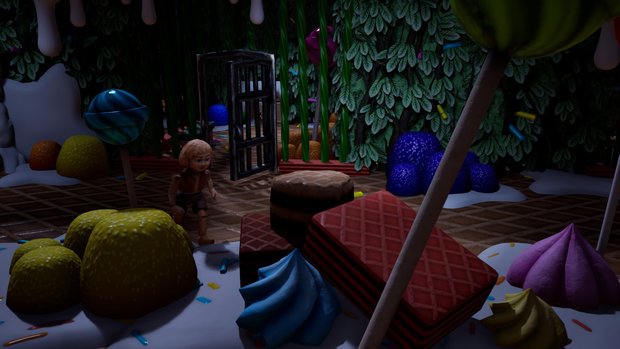

While some elements here correspond to their folkloric origins—you first meet Snow White after she has already been poisoned by the evil queen’s apple, for instance—in other ways they are sometimes quite different from any tellings of these tales that I am aware of. There is also a modicum of character complexity: Hansel and Gretel have differing feelings about their parents abandoning them; and while the wolf does seem scary, and he did destroy Hayward’s home, he is also depicted as an anguished figure, with hints that all may not be as it seems. Aside from this nuance, and any further revelations throughout the game that place matters in a new context, Once a Tale does not feel like a deconstruction or undermining of fairy tales, its tone instead quite rooted in the soft expressions of children’s storybooks. The result is a narrative that maintains much of the feeling and many of the hallmarks of these tales—trails through the woods made of pebbles, a candy-coated climax, etc.—while taking its own unique, charming shape.

The interface will likewise feel familiar to those who have played other 3D puzzle-platformers. I sampled the keyboard controls, which seemed to work well enough, but I played mostly with a gamepad, per the developer’s advice. You move with an analog stick or the WASD keys. There is a jump button as well a catch-all “interact” button—what this latter command does differs based on the context, at various points picking up, dropping, throwing or moving items, at other times performing unique abilities specific to each child. There is also a button with which you can switch between the two playable characters at any point in time. Hansel and Gretel can travel together but in certain areas, holding this button will allow you to separate them, which is necessary to solve certain puzzles. Overall, it’s a simple and streamlined control system that gets the job done without overwhelming the player with tedious nonessentials.

In terms of gameplay, Once a Tale doesn’t stray too far from the puzzle-platformer model, though it does offer a limited versatility within that framework. There are plenty of Zelda-esque puzzles that involve figuring out how to keep weight-activated switches on the floor down with large boxes and such, often through separating the siblings. There are moments when a surface you can’t reach by jumping alone will need to be accessed, necessitating you to create an intermediary platform with something nearby in order to proceed. At other times you’ll be collecting odds and ends, such as the bales of hay the littlest pig needs at the beginning. Despite sticking close to a well-trodden formula, the gameplay does not feel overly repetitive. And while the game is not particularly challenging for the most part, there’s enough meat to the puzzles to keep things engaging and fun.

A bit of low-stakes stealth here and there fleshes the experience out quite nicely. These include a brief segment where you must evade the wolf and an extended part where you sneak around a giant ogre’s home. In each of these, various parts of the environment generate noise—miscellaneous objects that can be knocked down, bells that ring out when touched, creaking floorboards, and the like. The need to avoid not only being seen but also heard makes navigating these moments just tricky enough to keep you immersed without becoming overly difficult for adventurers who may be averse to danger. Also, while failure is possible in these and a few other parts of the game, it’s immensely forgiving, letting you resume play at virtually the same spot.

Hansel and Gretel play with differences, and they receive near-equal attention throughout. Being the younger sibling, Hansel is small enough to crawl through narrow passageways, while his big sister Gretel is strong enough to pull herself up to platforms whose edges can be reached but that are too high to jump onto. (A neat little flourish: if you try to leap to these higher platforms as Hansel, he will grab hold of the ledge, struggle for a moment, then fall, unable to lift himself.) As you work your way through to the end, each child will acquire a couple of other abilities, including projectiles with differing names but more or less the same functionality. To use these, you hold down the interact button, which depicts a potential trajectory with an arcing line. You adjust your aim with the analog stick and release it to shoot.

For most of the game there is little to nothing resembling combat, but there is a multi-stage boss fight in the final moments. Given the projectiles Hansel and Gretel come to possess, the developers easily could have created a standard action encounter in which the children dodge attacks from an enemy, looking for openings to get in shots of their own. Instead, these offensive capacities are used sparingly here, the emphasis placed on elaborate puzzles that make excellent use of the area in which the fight occurs. It’s an incredible sequence, one of the best puzzle-driven boss fights I’ve played and my favorite moment of the entire game. Thrillingly paced, it escalates the challenge just enough to make for a rewarding finish without feeling abrupt and unfair. It also features some of the best animation in a game, replete with beautiful stop-motion.

On the subject of stop-motion animation, it is by far the greatest strength of Once a Tale. The set designs were initially created physically, utilizing recycled cardboard, long screws that serve as tree trunks, and other everyday materials. Digitized versions of these sets form the world within which the hand-crafted characters live out their drama. The exterior scenes are inspired by the Canadian wilderness of Quebec, where the game was designed, lending the atmosphere a sense of local distinction. Environments are varied enough to avoid a repetitive feeling and create a sense of contrast. The lush verdant greens of the forest do well to complement the dark, cloistered tones of multiple underground locations. The part set in the giant ogre’s home is especially memorable, the children navigating through stages of oversized furniture and household objects and at one point through spider-infested walls. A part near the end is set in a prison constructed of candy. Such a vibrant locale, with its licorice arches, candy cane wiring, and platforms made of ice cream sandwiches in opposition with the tension of the situation, makes for a stunning rush to the finale.

The puppets are animated at a slower frame rate than everything else, helping to replicate the familiar movements associated with stop-motion. While clearly not made with an enormous budget, there is an admirable attention to detail in the animation, with small but impactful gestures bringing things to life: blinking eyes, the fluttering of Gretel’s dress as she leaps. There is also great work done with body movement and posture. The children run, jump, stoop beneath low-hanging branches, and fit themselves into a giant pair of shoes—perhaps not with the most fluidity you’ve ever seen in a game, but with more than enough for the context. It all adds up to a charm and warmth reminiscent of an old Rankin/Bass TV special.

A word or two should be given to the use of lighting and depth throughout Once a Tale. There’s a fair amount of contrast between light and dark settings, which serves the story very well. But there’s also an impressive amount of variation in lighting within individual scenes, along with a remarkable depth of field that makes for a rich and cinematic feeling. As the children wander through the forest, streams of light extend down in sparse, slanting patterns, washing portions of their path with illumination and leaving others in darkness. As you walk along, a butterfly might drift by in the foreground, enlarged from your foreshortened perspective. At one point Hansel climbs through a narrow tunnel, the camera switching to a front view—all is dark until he finally approaches the golden light at the other end, the tunnel extending behind him beyond where we can see.

A strong score and sound design further enhance the cinematic aesthetic with great effectiveness. The music utilizes a wide variety of orchestral instruments to craft a soundscape very much like what you might encounter in an animated motion picture. A recurring theme that plays as the children travel between locations is wholesome and heartwarming, with expansive strings and woodwinds that hint at nostalgia. At other times, the music is tense and terse, like during an early encounter with the wolf, where sparse, isolated beats on a drum signify a sense of danger lurking dormantly. Sometimes the music is dreamlike, harp notes drifting in peregrine patterns as you ponder puzzles in a dungeon. Whatever the mood or energy, the score is always a perfect fit to the moment. Sound effects and small flourishes when you pick up items, switch between the characters, etc., provide a nice sense of fullness. There is no voice acting; while it would have strengthened the experience even further, cutscenes and dialogue are handled elegantly, with still images and text on paper-like backdrops, in line with the game’s storybook appeal.

As good as it looks and sounds, there are a few rough spots around the edges of Once a Tale that at times detract from the experience. For example, anything involving aiming or throwing functions somewhat gracelessly. Take, for instance, a moment early on when the characters are instructed by Hayward S. Pigue to toss bales of hay into a wheelbarrow. I found it a bit tricky to gauge exactly how far away I needed to be to get the hay to land in the desired spot, and when I did, it had a tendency to bounce out onto the ground. The game did count this as a success and allowed me to move forward, so it wasn’t really a problem functionally, but it just felt kind of sloppy. The more precisely controlled projectiles the children acquire later in the game (a sling for Hansel and a sewing needle for Gretel) work well enough, but adjusting the aim with these items is a slow, unintuitive process. Moreover, their range is quite limited, meaning you may need to move a couple of times before being able to hit something despite seeing it right in front of you. And when you do, you might find the camera switches before you can take aim.

Let’s talk about that fixed camera. It’s not all bad—in fact, it allows for some stunning, beautifully framed shots at crucial moments in the narrative. It also brings with it a slew of problems that most people who played 3D games in the ’90s and ’00s will be familiar with. Sometimes you’re heading in one direction, only for the camera to suddenly leap to the opposite side so that you immediately run back into the previous view. It also makes navigation a bit confusing if a passageway or door is small or shown from a weird angle—there were definitely a few times I caught myself with my thumb on the right analog stick only to remember that wouldn’t help me orient myself. At certain points, such as the final boss fight, an isometric approach is employed—parts of the game might have worked better if they had done this more frequently, particularly in certain puzzle-heavy areas or those where you need to find your way. All of that said, neither this nor the other issues I’ve cited meaningfully impede progress. They just make the overall product feel a little less refined.

Final Verdict

With Once a Tale, Carcajou Games has created an immensely charming game that is at once rife with beloved echoes of fairy tales and folklore, and at the same time its own invention. It has some design and camera problems, most of which do not affect function but do make the overall product at times feel unpolished. Fortunately, those interested in puzzle-platforming gameplay should find plenty to keep them engaged on their way to an immensely smart and well-crafted conclusion. Furthermore, anyone passionate about stop-motion animation should be delighted to work their way through a lovely world expressed in cinematic terms, with excellent animation and a fantastic score. For me, this aesthetic mastery and command of gameplay when it matters the most more than makes up for any relatively minor weaknesses along the way.

Hot take

Once a Tale more than compensates for some rough edges with gorgeous stop-motion animation, solid puzzle-platforming gameplay, and a strong finish.

Pros

- Warm-hearted fairy tale story at once familiar and unique

- Beautiful stop-motion animation with hand-crafted puppets and sets

- Strong and immersive score and sound design

- Engrossing cinematic atmosphere

- Solid puzzle-driven gameplay throughout

- Clever, creative finale

Cons

- Some presentational awkwardness, particularly with throwing objects

- Fixed camera creates some wonkiness

- No voice acting

Andy played Once a Tale on PC using a review code provided by the game's publisher.

0 Comments

Want to join the discussion? Leave a comment as guest, sign in or register in our forums.

Leave a comment