OU review

- 0 Comments

You owe it to yourself to check out this gorgeous meditation on the transformative power of storytelling

OU’s description on Steam compares navigating its setting to traveling through “a mysterious world constantly changing like a book whose pages are flipped out of order.” It feels appropriate, then, that it takes playing through the game—and then playing through it a few more times—to get a handle on the purpose behind this gorgeous, charming adventure. But while getting there can be a bit puzzling (and not exactly in the way to which adventure lovers are accustomed), what is ultimately found at the other end of the journey is an intelligent, touching meditation on the importance of narrative art and the transformative powers it possesses. It features beautiful, hand-drawn artwork, music both technically impressive and masterful at mood-setting, and an attractive mixture of casual gameplay with a few environmental puzzles and episodes of engaging but easy combat. Some aspects do warrant criticism, particularly an over-coddling hint system and some questionable organization of the game world that hinders immersion more than is necessary. But given how little OU demands in terms of difficulty and length, the positives more than compensate for the negatives, making it well worth the time of anyone who loves adventure games, children’s books, or storytelling in general.

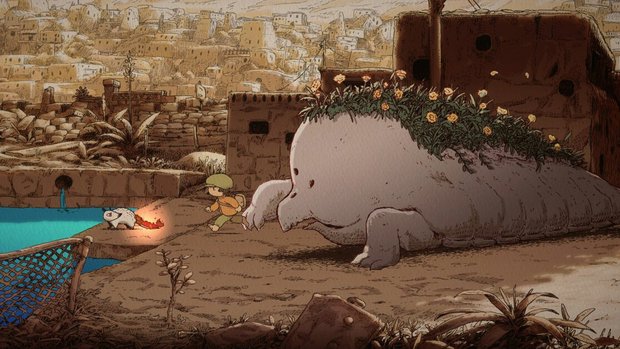

It all starts when a friendly if snarky opossum named Zarry happens upon a young boy asleep at the bottom of a bridge. You are this boy, and you are in quite a predicament; having lost all memory and sense of identity, you have no idea where you are or why. Zarry says you are in a land called U-chronia, and it soon becomes apparent that this world operates under a fragmentary logic, like a dream or a memory. There are various rules—such as the fact that diving into pools of water takes you to new locations—that even Zarry does not understand, and some he seems to learn only through epiphany. Nevertheless, he offers to serve as your guide, suggesting that traveling through the various parts of U-chronia might uncover the mystery. You see, Zarry’s tail intermittently bursts into flames that point in a particular direction, so he knows how to get around. He warns you of the Saudage, a monstrous specter that stalks the land devouring all that it sees, and with him you set out exploring.

Zarry’s flaming tail winds you through several locations, including forested areas, a town square featuring a lively mariachi band, a library covered in snow, and a rooftop above which a bed hangs from vines that grow from a green moon. Each new locale seems completely unrelated to the one before. You’ll meet various figures, such as a mysterious girl in a hospital bed, the Mexican folkloric ghost La Llorona, and a painter known as the Seer said to be responsible for creating everything throughout U-chronia. You also have encounters with the Saudage, which you must run from at points and fight off at others. Somewhere along the way, Zarry is compelled to give you the name OU. Eventually the two of you run across a mysterious stranger with whom you share a special connection—and who has a disturbing suggestion for how you might uncover your identity.

This is the premise for one playthrough of OU, but after I had made an integral choice at the end and watched the credits roll, the game informed me that I had uncovered just one layer of the story and needed to play it through again to glean more. The second playthrough starts off almost identically to the first, except that Zarry is aware of his previous encounter with OU and intersperses wry comments about this fact amongst his scripted dialogue. About midway through, however, the tale veers in a completely different direction, featuring unique goals and centered around an entirely different antagonist. The third playthrough has a decidedly meta bent, and while it is best left to experience rather than to read about, I will say that it ties together the prevailing mysteries in a satisfying and tender fashion. And while it may seem a daunting endeavor to get through all of this game’s incarnations, it only takes three or four hours to play through all of them.

There’s a paradoxical quality to the narrative content of OU that makes it challenging to evaluate. On one hand, there’s quite a lot of world-building and layers at work; on the other, very little actually happens. There is a commentary on storytelling that steadily comes into focus and features heavily in the final act. But OU isn’t so much a story itself as it is the space in between the big beats of one—the place beneath a story, you might say. It feels something like wandering through a writer’s mind, through pieces of an unfinished draft, almost coming into cohesion but ultimately being rejected in favor of further exploration. In this sense, it’s more a meditation on the raw power of narrative than it is a narrative itself. Some may wish for something more traditional, but what OU offers is undeniably fascinating and thought-provoking. I found it beautiful, in its odd little way.

While the storytelling might be experimental, the interface is not. On a keyboard, you navigate using WASD, or you can use the directional keys, pressing shift to run. You carry a set of sticky notes that you can place on various objects with the same key used for dialogues and miscellaneous other interactions. You can also throw a sticky at out-of-reach objects by holding the space bar, adjusting the trajectory with the directional keys, and releasing to let it fly. The stickies you place will make various notes on your surroundings, often presented in an abstract or poetic style—this is entirely optional but an enjoyable source of flavor. There are points, however, where it is necessary to use the stickies to knock over certain items to solve puzzles. They are also your only means of offense during a few boss fights scattered throughout the game. Overall, the control system does what it needs to with fluidity and ease, functioning similarly and working just as well on a gamepad.

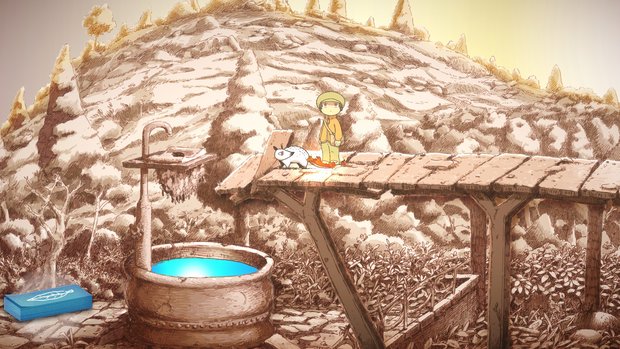

Gameplay is mostly driven by exploration. U-chronia is divided into several small self-contained settings, all of which have titles like “The Snowy Library” or “The Forest of Construction.” When you come to a body of water (in some instances, other liquids; in one scene, various paintings), you can jump in to reach a new location. In a clever marriage of theme and form, the game will ask at this point if you want to go to the next page. At the top right corner of the screen, an array of boxes will keep track of the pages you’ve been to—the ones you haven’t will remain blank until you visit that area. Generally, once you go to a new area you cannot backtrack, but there are exceptions, such as an underground chamber with multiple pools of water. When you reach the last page, you are able to cycle through to the beginning. It’s interesting that a game with a focus on nontraditional storytelling is so linear in its navigation, but it is fitting in the sense that it reminds one of books, read as they are, typically, from beginning to end—though when you finish one, you could choose to read it all over again.

While the manner in which the world is divided into smaller segments makes sense and is tied to the game’s themes in an inspired way, it is also the source of my core criticism of OU. You see, whenever you travel from one page to another, not only are you greeted by a loading screen, but the score fades to silence, another piece of music beginning once the new scene has loaded. To be fair, the loading screens are adorable—with content like a detailed drawing of Zarry diving through a pool of water—and you won’t spend more than a second or two between sections. The problem is that you spend so much time traveling between locations, often only in one for a matter of seconds, these interruptions accumulate at such a rate as to become barriers to immersion. This had the effect of really drawing me out, especially in the earlier parts, before I was invested in what was happening. Eventually I felt consistently engaged, but it took me the entire first playthrough and about half of the second to get there. I can’t help but think there are ways this world, or perhaps the tasks within it, could have been organized to be more immersive.

You can almost always talk to Zarry, who usually has at least one novel thing to say about each scene and often chimes in unprompted with comments, observations, and guidance anyway. He’s also an immensely charming presence throughout, and by the end I felt quite bonded to him. Aside from Zarry, there are a number of other characters you will encounter along your journey. Though interactions don’t always advance the plot, they are colorful and fun all the same. A mariachi band comprised of other opossums joke around with Zarry at one point, and another memorable sequence involves a shark circling through the sky. La Llorona is a particularly intriguing presence due to the fact that she is drawn from real-life folklore rather than an invention of the writers, as the others seem to be. This works well with the self-aware elements at play, providing an anchor to the outside world.

At certain points you will need to solve a puzzle to open up a passageway or clear an obstacle. Typically these are incredibly simple, and they almost always involve throwing a sticky at something. Occasionally there are meatier puzzles, such as needing to deduce a code for a doorway from clues hidden nearby. These might provide a bit more sustenance for players hungry for a challenge—but only those who can solve them with immense speed. OU has a built-in hint system in the form of Zarry, who must have cut his teeth on unused adventure game puzzles floating around U-chronia, because he figures these out in lightning quick fashion and apparently has no patience for those of us who need to spend a little time with them, blurting out revealing clues—and then entire solutions—within, say, a minute or two. I appreciate why this mechanism exists, but it seems like something more seasoned players should be able to turn off, though puzzle solving isn’t enough of a focus for this to detract too much from the overall experience.

The various encounters with the Saudage offer some effective genre-bending in the form of (light) action and (even lighter) survival horror. Whenever the monster draws near, Zarry freaks out and runs away, as a foreboding cello motif hijacks the score and footsteps reverberate in the distance. Usually the Saudage chases you. It moves pretty slowly, so there’s plenty of time to get out of the way. But if it does get you, it will gobble you up, sending you to oblivion. The stakes are pretty low here—oblivion functions as another area of the map, with a convenient pool of water to take you back to where you were. Then you can better heed Zarry’s warning by scrambling away from the Saudage to the safety of a new screen.

At key moments, though, the Saudage will corner you, leaving combat the only viable option. For these fights it will change into a unique form, with a point of weakness that Zarry will clarify for you (because of course he would know that sort of thing). A few well-placed stickies will ensure defeat. Losing the battle is pretty much identical to getting caught during a chase sequence. I mentioned earlier that the second playthrough features a distinct antagonist—there are some differences in the details, but encounters with this foe work more or less the same way.

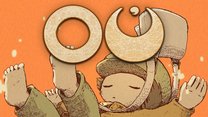

Even without the lack of consequence, the Saudage isn’t scary enough to put much of a dent in the OU’s warm-hearted atmosphere, but encounters with it do offer a fun tinge of suspense. It helps, too, that the monster has an incredible design, that of a grotesque land beast akin to a walking whale, a dense patch of grass and flowers growing from its head and back. It’s just the sort of creature that would be perfect as a villain in a children’s book. Its alternate forms are equally compelling and fantastical, such as when it changes into a giant bug with menacing, beady eyes that peeks from the pages of a tattered book held together by cobwebs. Another character design bearing mention is that of La Llorona, whose pale dress blends together with her pallid face, consumed by a vast hole that completely hides her features. It’s very striking and perfectly symbolizes grief.

But really this is just skimming the surface of how jaw-droppingly gorgeous this game is. Even those not attracted to the gameplay or story might find it worth spending time in U-chronia if only to marvel at its stunning hand-drawn art. With highly detailed backgrounds, pretty much everywhere you go oozes charm and style. The color palette renders much of the world in sepia, with character models depicted in bolder colors, as well as patches of the backdrop. The effect is subtler than I’ve seen in other works; rather than call attention to itself, it is just yet another element that eloquently reinforces the game’s thematic material, conjuring the image of an old book with fading pages.

There’s also an impressive amount of diversity, both in tone and type of location. Some areas exhibit whimsy, such as Sandwich Hill, a mound of earth held up by branches that extend into the sky, with a giant sandwich sitting on a picnic blanket in the corner. Other environments are darker, with a more tortured feeling, such as one backdrop that is almost entirely comprised of an enormous doll made of thick, twisted branches. Excellent work is done with lighting and reflections: a green moon that shines on the sea, or the warmth of Zarry’s fiery tail that brims brighter, even, than daylight. On top of all that, admirable care was put into character animations, which move fluidly with full body motion.

The score is exquisite, too. For the most part it consists of a selection of music for acoustic guitar. Some tunes are lively and jaunty, others moody and languid. One recurring theme evokes a hazy feeling of nostalgia, perfect for the odd little place U-chronia is. It’s all masterfully performed and well-recorded, and regardless of the vibe, the music always flawlessly complements the atmosphere. At key moments, the guitars give way to other instruments, such as the cello part I mentioned that announces the arrival of the Saudage. Sometimes the game plays unaccompanied by music, creating a reflective feeling. Sound effects such as footsteps or doors opening help to flesh out the sound design. There is no voice acting, which feels less like a limitation here than a stylistic choice.

Final Verdict

The aesthetic strengths of OU—its sights and sounds and style—are abundant enough to do most of the heavy lifting, yet the game as a whole is a truly unique experience with multifaceted world-building, lovable characters, and great poignancy throughout. It takes laudable risks in its storytelling, constructing a fascinating and thought-provoking narrative on its own terms. To be sure, there are ways it could have been improved—a little less hand-holding, a touch better organization—but there is no shortage of fun to be had in exploring U-chronia. OU is a game that wants us to believe in the power that narrative and art possess. It may not demonstrate that power perfectly, but it certainly does so with a surplus of beauty and charm.

Hot take

OU deserves enormous credit for its superb art and its distinct, ambitious style of storytelling, providing a memorable high-concept experience only slightly hampered by questionable design choices.

Pros

- Thoughtful, moving commentary on the importance of storytelling

- Fun and varied cast of characters

- Fascinating world-building

- Gorgeous art with unique style evocative of children’s literature

- Masterful score mostly by acoustic guitar

Cons

- Abrupt segmenting of game world, frequently interrupted by loading screens, makes immersion more difficult

- Overzealous hint system subdues any meaningful challenge

Andy played OU on PC using a review code provided by the game's publisher.

0 Comments

Want to join the discussion? Leave a comment as guest, sign in or register in our forums.

Leave a comment