Scott Whiskers in: the Search for Mr. Fumbleclaw review

- 1 Comment

An otherwise fun adventure will leave you bristling at the mishandled excess of dialog

Scott Whiskers is an inveterate pet lover. He works for an animal shelter and would do anything to help a pet, even when it’s not his own. It’s that compulsion that propels him on a quest to find the missing titular cat in Scott Whiskers in: The Search for Mr. Fumbleclaw. Fancy Factory’s hand-drawn 2.5D point-and-click adventure strikes an amusing tone with its premise, cast of characters, and assorted tasks that its hero must do. And for the most part the game is engaging, except when characters start to talk. And talk. And talk. And. Talk.

Scott Whiskers opens with a playable tutorial set in the protagonist's apartment. This section, though brief, does not put the game’s best foot forward. First Scott has to fix his front door with the door handle hidden, for no apparent reason, somewhere it would have no business being. Doing so causes the state of the game world to change so that another needed item appears, again with no reason, in a place you may have already searched and that has no causal link to the door. Fortunately the rest of the game is largely devoid of such randomness, but it’s a baffling introduction that is far less fun and more nonsensical to play.

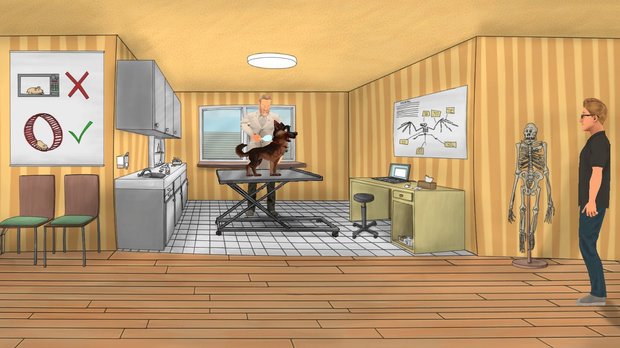

In the game proper, Scott’s day starts in a mundane way. He’s supposed to have the day off, but then his boss from the animal shelter calls because she’s in dire need of help with the animals. Scott simply can’t say no. While he’s at the shelter, he learns of the disappearance of Mr. Fumbleclaw, an award-winning show cat, whose owner cares more about the glory of victory than the cat himself. Scott refuses to abandon any animal, and so he sets out on the trail of Mr. Fumbleclaw, who may have inadvertently got himself stuck in a shipping container.

Scott’s journey takes him all over town via a fast-travel map, from the palatial Longbottom estate that Mr. Fumbleclaw escaped from, to the dark alleyways of the black market, to the pet salon, police station, a movie set, and even a creepy old house where it’s perpetually night. The variety of locations is impressive. Equally impressive is the number of characters, as each of these places usually has multiple people to talk to, all with their own eccentricities. There’s the butler who’s engaged in making fur hats from the pet salon’s trimmings, and the video surveillance cop who plays Police Quest for the first time and comes to the conclusion that life is nothing more than a walking death trap. Then there’s a long-forgotten monster movie actor, a postal deliveryman who takes The Office waaay too seriously, and the Longbottom daughter who is forever trying to convince her dad to give her more money to fund her directorial ambitions. The list goes on, and all of the characters are well-delineated.

The problem with fleshing all these characters out so distinctly is the indulgent means by which it’s accomplished. Namely, the dialog. I have played games with lots of dialog, and the likes of Lamplight City or Murder on the Orient Express are nothing compared to Scott Whiskers. The game runs nearly eleven hours, and I have to believe that at least nine of those are spent talking. I timed several of the conversations. A single choice from a dialog tree averaged about sixty-five lines and took five minutes to play. For one dialog choice. Not the whole tree. Just a single choice. And while lines of conversation aren’t repeated, much of the content becomes very repetitious. The first time Lady Longbottom indicates a desire for Fumbleclaw to win the annual pet pageant but a disdain for the cat himself, it tells you everything you need to know about her. The tenth time, it starts to get a bit much.

After spending over an hour in back-to-back dialog trees at the Longbottom estate, I had to get up and walk away. I couldn’t just sit there and listen to the game anymore. I truly despaired over how I was going to finish playing. As I mulled over my experience to that point, it dawned on me that I’d uncovered a new type of game: the background game. Similar to how you might put on a TV show in the background while you work on something else, I realized I could do the same with this game. With this new mindset, I fired up Scott Whiskers again and turned my attention to one of my other pastimes, which is to draw. I listened to the dialog as I drew, and would return to the game to pick the next topic once the characters finished rambling about the current one. I had quite a nice collection of completed drawings by the end of the game.

Between the long stretches of player-agency-robbing dialog, there actually is a decent game tucked into Scott Whiskers. Most of the challenges consist of collecting and using inventory in typical fashion. There are a couple of instances of moon logic, with Scott himself even acknowledging the absurdity of one of them, but for the most part the difficulty is just right. At least it is if you’re paying attention to the objectives in the To Do list. For all the talking the characters do, it’s sometimes not evident what, if anything you need to do for them. However, the To Do list nicely summarizes what you should be working on without giving away any solutions. These interactive parts of the game, unfortunately, tend to not last longer than four or five minutes at a time before it's back to talking to another character, usually to find out what they’re struggling with.

Scott is always there to help solve problems for people he’s never met before. It’s a tendency he attributes to playing adventure games himself. He’s also a big science fiction and fantasy fan. Consequently, The Search for Mr. Fumbleclaw is full of pop culture references, nods to other adventure games, and fourth-wall-breaking moments. With his bubbly, ever-optimistic attitude, Scott’s a fun character to hang out with. His references are all made rather tongue-in-cheek and make for a generally amusing experience, even if actual laugh-out-loud moments are rare.

With Scott Whiskers featuring so many locations and characters, something was bound to give in this indie game, and it happens when Scott has to carry out some manner of physical activity. At various times, the game employs the two traditional cost-saving methods for cinematics: It either just has something instantly happen, like one object being replaced with another without Scott animating to do anything, or it uses the fade-out method. The screen goes black, Scott expounds on what’s actually happening, then the scene fades back in. A couple of times, after the completion of one of the bigger puzzle chains, a cinematic is presented as three or four still background images while Scott narrates.

Visually the backgrounds and objects are hand-sketched and vividly coloured, suiting the protagonist’s own upbeat positivity. Characters are rendered as 3D models on top of the backgrounds, using what’s known as an “orthographic” representation. That’s just a fancy way of saying they’re drawn without perspective. I tended not to notice too much except for the characters’ feet, which are always parallel to the bottom of the screen rather than being angled to match the perspective of the scenes. This can make it seem like the characters are floating over the environments rather than a part of them, but only occasionally.

Audio-wise, Scott Whiskers has a musical score vaguely reminiscent of Monkey Island mixed with Day of the Tentacle, which helps add to the humorous vibe the game’s going for. Background effects do their job, sounding like the things they should. Kudos go to the voice actors, first for just getting through the sheer mountain of dialog they had to record, and second for doing quite a good job of it. The only minor complaint is that all the actors tend to speak very slowly, which compounds how long the dialog drags on. Incidentally, the developer himself seems to have recognized just how much time is spent in conversation, as the options allow you to play the dialog at up to 125% normal speed. (You can also slow the dialog down, if the game isn’t long enough for you as is.) While I would have liked to avail myself of this option, I chose not to so that I could report an accurate play time.

Final Verdict

I’ve never agonized more over the final verdict for a game than I did with Scott Whiskers in: The Search for Mr. Fumbleclaw. The playable part of the game is quite fun. There’s an eccentric cast of characters to interact with, puzzles that are just hard enough to require thought without bogging down proceedings, and the visuals, while nothing spectacular, cheerfully get the job done. If that was the extent of it, this would be a good, solid adventure. The only but, and it is a BIG but, is the run-on dialog. Having a game consistently take interactivity away for such long periods of time defeats the purpose of making it a game in the first place. And while often lightly amusing, the script here isn’t so riveting as to command many long hours of attention on its own. It all ends with a hint that a sequel, The Search for the Golden Cat, is coming in the future. If that game can get the dialog down to fighting trim, I would welcome it with open arms. But we’re not talking about that game, we’re talking about this one. And as much as it pains me, without serious editing I have to recommend leaving poor Mr. Fumbleclaw lost in the wilds.

Hot take

Bloated dialog bogs down what’s otherwise a fun search for a missing cat in the lightly humorous Scott Whiskers in: The Search for Mr. Fumbleclaw.

Pros

- Eclectic cast of characters

- Voice acting is good

- Puzzle challenge is mostly spot-on

- Lots of different locations to search

Cons

- Tutorial gives a poor first impression

- Many hours of overwritten dialog take player agency away for too long

Richard played Scott Whiskers in: the Search for Mr. Fumbleclaw on PC using a review code provided by the game's publisher.

1 Comment

Want to join the discussion? Leave a comment as guest, sign in or register in our forums.

Thanks for this excellent review, Richard. I was going to purchase this game one day soon, but the extremely extensive dialogue makes it a no go with me. The real secret of Monkey Island is that Guybrush and the citizens of Melee Island (and islands thereabouts) rarely ever speak more than one, maaaaybe two, lines of dialogue at a time. The conversations are short and sharp. Less is more, the player asks a question and gets a snappy, well written answer. We're typically left wanting more, not less. So many adventure game authors don't get this: Writing well so often means writing less.

Reply

Leave a comment