From Ink to Pixels: European Graphic Novels Turned Video Game Pioneers, Part 1 – Salammbô

- 0 Comments

When it comes to video game adaptations, for many people the terms ‘comic book’ and ‘superheroes’ are largely interchangeable – or at least they were in decades past. Heavy Metal magazine, for example, curated a selection of the best graphic novel content from Europe over the course of its forty-plus year run. That said, action-packed video games based on comic book superheroes have historically been far more prolific than titles based on non-superhero properties.

That began to change slightly in the early 2000s when some of Europe’s most celebrated comic books were adapted into video games, with not a cape or cowl in sight. These games were well-suited to the adventure genre, stressing storytelling over action. What’s more, the original creators of several IPs had a hand in the development of the games based on their work. Some of these cross-media endeavours turned out quite well, while others failed to find their footing in the new digital medium. This multi-part series will highlight the three pioneering games that stand out in my personal experience as the most interesting interpretations of their source material. They may not have left much of a lasting impression in their own right, but they helped blaze a trail for other comic book franchises to succeed where their predecessors did not.

Salammbô

Phillipe Druillet was one of the founding members of the French magazine Métal Hurlant, first published in 1974 before being brought over to the United States by National Lampoon under the name Heavy Metal three years later. Druillet’s own Salammbô was one of the publication’s most notable early works, reimagining Gustave Flaubert’s nineteenth century epic about Carthage as a space opera.

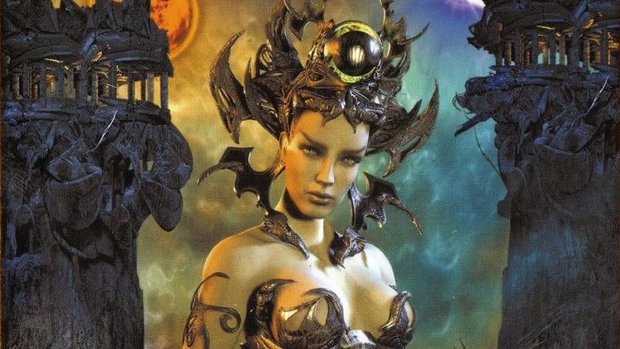

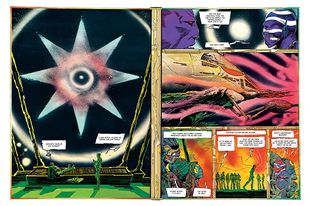

Druillet’s fantasy universe is a mutation between ancient architecture and intergalactic science fiction, with gargantuan structures radiating neon hues floating in the vastness of space. Characters are gaunt, almost demonic-looking, and wear armour so intricate and detailed you’d think Druillet secretly had a treasury of Carthaginian artifacts to reference. Entire pages, sometimes even two-page spreads, show armies clashing over dark surreal landscapes that are as nightmarish as they are beautiful. Though it may seem like a drastic departure at first glance, a quote from Druillet in the introduction to the 2018 edition of Lone Sloane: Salammbô reveals that he didn’t think Flaubert would have felt betrayed by his “lighting Salammbô’s face up a bit with a laser beam, because I love his sublime novel with a passion.”

The battle for notoriety in the adventure genre (and for Carthage, too)

Around the turn of the millennium, Cryo Interactive began work on an adventure game adaptation of Druillet’s work. Originally titled Salammbô: Peril in Carthage, the game was to be an interactive rendition of the graphic novel. Druillet would oversee the game’s artistic direction, working closely with the development team on designing the environments.

Unfortunately, Cryo closed due to financial troubles in 2002. However, DreamCatcher Interactive bought up several of their properties and resumed development of Salammbô, ultimately releasing the game in 2003 under the new name, Salammbô: Battle for Carthage.

In Salammbô, players assume the role of the slave Spendius. In an exciting opening segment, Spendius escapes his cell only to run into the eponymous princess wandering the streets at night. To Spendius’s surprise, instead of turning him over to the authorities, Salammbô sees his potential as an ally, asking him to deliver a message to her lover, Mathô – a mercenary formally employed by the kingdom. Spendius agrees, and his adventure begins.

Salammbô sends players through a variety of locations in the harsh desert surrounding the city, as well as the labyrinthine streets and sewers beneath it. Spendius slowly works his way up from messenger to soldier, gradually undertaking more and more dangerous missions, including stealing from the palace to win Mathô’s trust, eventually even heading an army.

Mini-games are strewn throughout, testing players' reflexes with tasks such as shooting a bow and arrow, and challenging their tactical skills by moving army units across a map like chess pieces. However, the game is still a point-and-click adventure at heart, focusing more on navigating dialogue trees and solving logic and inventory-based puzzles blocking Spendius’s way. The game rarely stalls in introducing new puzzle segments thanks to the ever-present story elements and large cast of characters.

Though the environments are striking and ripe for exploration, the omnipresent feeling of danger remains thick throughout. Several sections implement time limits, forcing you to think on your feet while moving forward in order to avoid one of the game’s many grisly ‘Game Over’ screens, like when you are forced to circumvent a canyon environment looking for food while racing against a quickly depleting hunger metre.

Most of the action is controlled from a first-person perspective via node-based movement, with 360-degree camera panning allowing you to search each waypoint thoroughly. Despite being pre-rendered, the environments are all animated, with details like the flicker of torches, running water, and swelling clouds painted in radical neon colours making each predetermined station worthy of stopping to appreciate. Full-motion videos are sprinkled conservatively throughout, with narrated comic-style cutscenes appearing regularly as you complete different objectives, calling back to the storytelling medium of the source material.

Characters are fully voiced, giving each interaction a deeper level of immersion. They too are adorned in spectacular garments and armour, conveying a society that is both dangerous and seductive. Guards have thick-plated uniforms covered with intricate markings, while others wear barely any clothing at all, like shrine maidens with their iron braziers molded after cupped hands. Many characters have glowing, pupil-less eyes, giving them a ghostly impression and making their intentions hard to read.

The sound effects too lend each area a convincing level of authenticity, with details like the howl of the city’s elephants occasionally heard in the distance. Though parts of the game are spent in (relative) silence, an orchestral score does come in from time to time, namely during climactic segments like the military campaigns. These arrangements suit the game perfectly, with the beating drums and chanting choir lending the game an epic aura.

Failed incursion

Salammbô: Battle for Carthage was largely praised upon release. Tap-Repeatedly commended the game’s thoughtful puzzles and lack of backtracking, calling it a “refreshing alternative to the usual generic Egypt-Atlantis-maze-sliding-tiles pabulum we’ve been force-fed for the past few years.” Just Adventure criticized Spendius’s lack of likeability, but praised just about everything else the game offered. Despite the generally positive critical response, however, Salammbô didn’t sell as well as anticipated, so DreamCatcher decided not to move forward with their intended sequel.

It’s a shame that Salammbô: Battle for Carthage didn’t succeed, as it’s a solid adventure game that I really enjoyed. Though it discarded the space opera setting of Druillet’s original, the artist’s distinct visual style impeccably fits the game’s more rooted – though still fantastical – ancient Carthaginian setting. The city’s mysterious history allows for a greater degree of speculation and invention, and the designers took full advantage by constructing a world brimming with detail. The timed mini-games may be somewhat divisive, but I personally like the puzzle variety, and feel they keep the game from lagging in any one section. The pacing and generous save system also prevent it from becoming too overwhelming, encouraging experimentation with different approaches while maintaining suspense.

However, uncovering more of the story is what ultimately kept me glued to the screen. The multitude of characters and locations were created with such care that I found the world to be absolutely intoxicating. Even setting gameplay completely aside, Salammbô: Battle for Carthage is worth playing – or at least watching a playthrough – just to soak in the radical vision Druillet and DreamCatcher fashioned.

Salammbô: Battle for Carthage has been re-released digitally and is available on Steam for Windows PC.

0 Comments

Want to join the discussion? Leave a comment as guest, sign in or register in our forums.

Leave a comment