Viewfinder review

- 1 Comment

Pretty as a picture and spatial solutions are a snap in this engaging 3D environmental puzzler

It’s interesting that in a medium where you can create worlds with seemingly anything in them and make pretty much anything happen (within certain technological limits), every now and then a game comes along that feels like a real magic trick, that makes you think, “Wait, you can do that?!” I’m thinking of games like Portal or Antichamber, or more recent marvels like Superliminal or Manifold Garden. Viewfinder, a first-person puzzler by Sad Owl Studios, fits well within that lineage, dazzling its players with optical illusions and a mechanic that lets you reshape the environment with impressive freedom. While I can’t help but wish that the design space had been more fully explored with deeper challenges or richer storytelling, I also wouldn’t hesitate to recommend this game for what it is: a brief but highly entertaining tour of visual wonders and playful scenarios overlaid with a story of scientific optimism and world-saving ambition.

When I first saw the trailer for Viewfinder, the central puzzle mechanic certainly looked intriguing: you can hold up a photograph into your view, click the mouse (or push a controller button), and any architecture and objects within that photograph suddenly become a part of the actual world before you, replacing whatever was obscured behind the picture. As clever as it seemed, I suspected that this feature would be highly restricted, allowed only within very specific instances when the developers saw fit to make it available, and likely with quite a bit of hand-holding so that you don’t break anything. About two minutes into the game, I was proven to be incorrect. You can break darn well whatever you please, and it’s a better game for it.

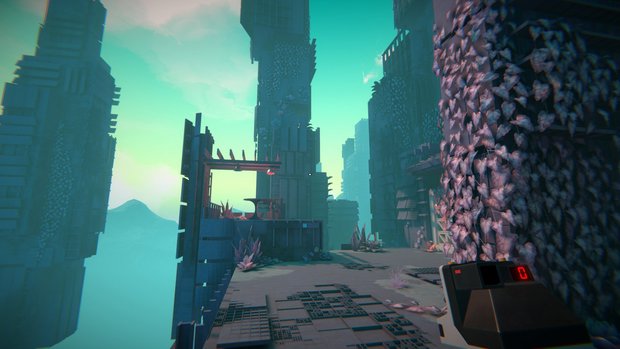

The setup is that you, the great nameless protagonist, have been transported by a fellow explorer into a virtual world created by a small team of scientists and visionaries who had it in mind to save the planet from climate disaster. They used the simulation as their canvas to experiment and invent, and now, mysteriously vacant, you are hoping to search the place, uncover their findings, and perhaps bring something back with you to help alleviate the Earth’s meteorological miseries. Naturally, they wouldn’t leave all of their helpful research in the front lobby where just anyone could wander up and learn from it. No, they do what any self-respecting scientist would do: hide it behind a gauntlet of spatial reasoning puzzles and call that “security.”

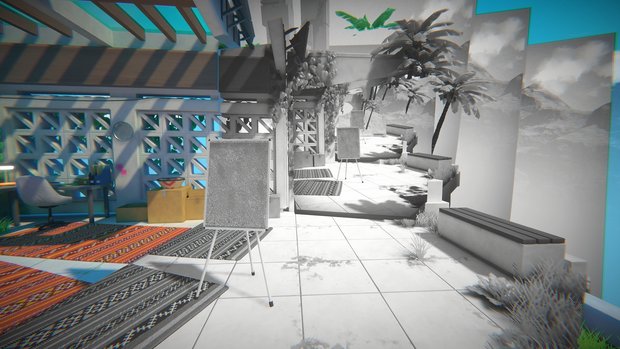

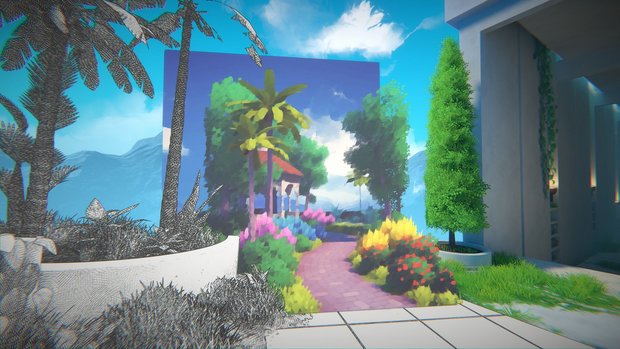

While it’s difficult to understand what, if anything, all of the visual trickery has to do with cleansing the Earth’s atmosphere, it’s also difficult to care a whole lot when you’re having so much fun twisting the world into knots. The very first instance of the photograph mechanic has you pressing a key to pick up a black-and-white picture of a walkway through some arches, with a machine sitting at the far end. You can hold this photo up in front of you by holding right-click, then place that scene into the world with a left-click, effectively obliterating anything that was blocked out behind the picture, all the way through to the sky in the background.

It’s hard to describe in writing, so be sure to watch the trailer below if you want to see it in action, but it’s a really cool effect in that there are almost no noticeable cues beyond a clicking sound that lets you know something happened. It still looks like the picture is just hanging there in front of you – until you start to move and watch the perspective shift, revealing that everything within the photo’s frame has now been incorporated into the environment, fully functional and joined into the surrounding architecture but keeping the same look as the original picture, which in the case of this first example is black-and-white. You can now walk down a real corridor projected from this photo and reach the machine, which serves as a teleporter to the next location.

To make this even more impressive, this is a fully 3D first-person game, so you can “place” these photos absolutely wherever you want: over any wall or piece of decoration, straight up over your head, immediately beneath you–you can even rotate the photo so that the whole thing is upside down or slanted at some odd angle. “But wait,” I hear you asking, “wouldn’t that allow you to mess things up beyond repair?” And the simple answer is yes. Placing that first corridor right beneath you would mean you would fall right down it and blow past your only exit. You can also place a picture over the exit portal or some other important switch or machine, erasing it entirely from existence – but only in the present.

To facilitate this free-form world-shaping mechanic, there’s a simple rewind feature that works just like Braid or other time-reversal games in that you can hold a button down and rewind anything you just did, at any time. You can even double-tap the key to fast-travel yourself back to the last time you made some kind of significant change to your surroundings. This feature is the one that really makes the other more impressive features shine, because without the fear of failure or needing to restart a level every time you make a mistake, you’re free to explore and try out your wild ideas, and the game is much more playful as a result. The developers have leaned into this, too: chances are that if you’re thinking, “I wonder what would happen if…” they’ve likely thought of it first, as there are a quite a few achievements included, at least on Steam, and I saw them popping up fairly often as I attempted to “break” the game by cutting structures and objects in half with the pictures or trying to create infinite loops.

Each of the five main locations in Viewfinder acts as a hub to a series of levels. The first four areas are the workspaces of the four founders, while the fifth is indicated by a question mark for most of the game, so it’s better if I don’t divulge. Within each area there are teleporters to the individual levels, with each teleporter leading to a string of maybe four or five levels, played in order, in which the goal is simple: reach the teleporter to the next level (or back to the hub world). You might do this by bridging a gap with a rotated picture of a column, or clearing away a wall using a photograph of the sky. Complete the levels in a location, and you can hop aboard a sky train to the next area.

The linearity and predictability of the overall structure belies a much more varied and even whimsical approach to the progression of the mechanics. The set of levels within one teleporter usually explores a particular theme or idea, often introducing a new aspect or twist on the gameplay. Some of these scenarios are better left as a surprise, but one of the more obvious evolutions is the provision of an actual camera, allowing you to take photographs yourself and then apply them elsewhere, like copying and pasting wherever you see fit, as long as you have the film – you’re usually given a limited number of snapshots in a given level. Other levels veer off of this central concept entirely, however, playing with various concepts of perspective and illusion. And even within a level, you’ll frequently stumble upon an Easter egg with its own self-contained idea, like a postcard for Stonehenge laying on a table that you can pick up and “place” into reality, allowing you to go explore and climb on the stones, once you maneuver past the giant words in the foreground. There’s no reason you *need* to do this – it’s just there for the fun of it.

The rapid pace of new ideas and clever mechanics allows for plenty of delight and discovery, but it does have the drawback of not always feeling focused. Around three-quarters of the way through the game, there was a brand new mechanic introduced that lasted all of three levels, and just as I was seeing its design potential, it was completely abandoned, never to be used again. Often it felt like the puzzles in a particular level set were just starting to get past the intro stage and into more difficult territory right before the game took another sharp turn and we were on to learning something else. That’s not to say there aren’t a few stumpers, but they’re mostly either late in the game or in a handful of optional levels that are spread throughout the areas in their own teleporters. I found these bonus challenges were actually some of my favorites, and I would have liked to see more of the main path following suit by providing trickier puzzles or more fully exploring its many ideas.

Speaking of exploration, the virtual environments of Viewfinder are visually striking, and I enjoyed wandering through the floating concrete structures and pavilions draped with greenery, adorned with paintings and decorative knick-knacks, and decked out with the kind of mid-century modern furniture that manages to look both inviting and uncomfortable. The models and textures aren’t highly detailed, but the design drew me into the space with blue skies and bold colors popping out against the neutral grays of the architecture, accentuated with a mellow, airy, synth jazz soundtrack. Each area is brimming with objects and decor that are reflective of their respective founder’s research specializations, like botany or engineering, as well as their personal interests, like painting or mahjong. As the game progresses, you gain access to several camera filters that let you personalize the way your photographs look and feel, and thus affect the resulting additions to the environment. If you want your surroundings to resemble a film noir, have painterly brush stroke effects, or be plastered over with a bunch of watermelons (?), the choice is yours.

There’s a story told throughout all of this, revealing more about the nature of the Earth’s predicament and the dreams and personalities of the simulation’s creators. First, there’s your energetic fellow explorer who has helped you get into the simulated world and serves as your disembodied guide and will comment on your progress and what she is doing outside of the program. Then there are the trusty audio logs, handwritten notes, and, oddly enough, copious Post-it notes of the team, providing insight into these four visionaries and their relationships to one another. Finally, what future-ville would be complete without a smooth-voiced AI embodiment (a sort of Cheshire Cat, in this case) that seems to follow you wherever you go? You can even pet it, too.

The voice acting of these characters can be over-earnest at times, and some of the dialogue leans a little cheesy, but it’s charming enough, and I sought out all of the logs (which are curiously housed in old phonographs) so I could hear how the characters progressed. Ultimately, though, while the story interested me, I was hoping for the kinds of surprises or insights that I felt would match a game about illusions and limitless world-building (Inception comes to mind), but the characters weren’t all that complex. And while there appeared to be something like a setup and a reveal, it turned out that they were “revealing” something that I had kind of assumed in the first place, so it never quite hit home, and the attempts for big emotions towards the end fell a little flat for me.

Another drawback is a game design misstep right at the end with a section of tightly timed puzzles. You have five minutes to solve and execute ten puzzles, and if you fail, you go back to the beginning to try again. This didn’t match the whole laid-back vibe of the rest of the game, and trying to execute these puzzles quickly was more of a stressful chore than a fun way to finish. Mercifully a setting is included in the options to turn the time off, although this isn’t directly mentioned until you fail a few times and I was already frustrated after my second failed attempt. Perhaps there are some who like the element of speed when solving puzzles, but I’m not one of them, and it didn’t seem to fit with the overall design. Still, it’s only a small percentage of the game, so don’t let that deter you from an otherwise highly enjoyable experience.

Final Verdict

Viewfinder has managed to capture something fascinating here. The composition is engaging enough that its few creases and smudges do little to detract from the spectacle of its subject. It’s admittedly not the deepest experience, but the briskly paced 4-5 hours of gameplay means there’s rarely a dull moment as the developers whisk you from one beautiful environment and clever idea to the next while still allowing you the freedom to experiment, explore tangents, and make a right mess of things just for the fun of it. Even with a fairly thin story, frustrating end sequence, and puzzles that tend to pull their punches, the fact that this will still land as one of my favorite games released this year is testament to the overall strength of the interactive wonders on display in this gem of an indie adventure.

Hot take

Viewfinder’s shining achievement is its brilliantly executed set of reality-bending mechanics that are such fun to play with that its tenuous story and relatively simple puzzles are easy to overlook.

Pros

- Wide variety of spellbinding mechanics and visual tricks

- Great rewind feature gives you the freedom to experiment

- Lots of playful scenarios, fun details, and Easter eggs to discover

- Striking visual aesthetic and world design supported by a soothing soundtrack

- Interaction between the fully voiced characters is charming

Cons

- So many ideas that they don’t all have room to be fully explored or become challenging

- Story feels a little slight and lacks surprises or emotional weight

- Timed end sequence is more frustrating than fun (although the timer can be disabled)

Brian played Viewfinder on PC using a review code provided by the game's publisher.

1 Comment

Want to join the discussion? Leave a comment as guest, sign in or register in our forums.

Thanks for sharing this helpful resource! I've bookmarked it for future reference.

Reply

Leave a comment