NORCO review

- 1 Comment

A down-to-earth, highly refined narrative adventure

Norco is a real place, a suburb of New Orleans located in the shadow of a massive oil and chemical complex. The petrochemical industry has dominated its landscape and economy for more than a century; its very name comes from the New Orleans Refining Company that first struck oil there. It's part of an area nicknamed “Cancer Alley,” an 85-mile stretch where more than 150 plants and refineries operate alongside (and within) residential communities. Decades’ worth of air pollution and chemical runoff mean disease, disability and premature death are facts of life there. Locals witness the devastation of their homes and environment in real time, while the threat of sudden explosive catastrophe hangs always in the air. Meanwhile the sea continues to rise, all but consigning the coastal and river parishes of Louisiana to oblivion within the next few decades.

All of this history—this reality—thrums just beneath the surface of NORCO, the debut title from Geography of Robots. The characters are trapped in a slow-motion apocalypse, caught between the worsening ravages of climate change and the oil companies' ever-escalating hunger for growth while violence and economic decay proceed unabated. Yet what choice do they have? This place is home. They must keep living, finding ways to survive and preserve the things they love while their families, their livelihoods, and their very bodies are stolen a piece at a time. NORCO is a game about making a life inside that waking nightmare—of enduring and moving forward as reality unravels, of pushing back however you can against vast and alien forces—and it beautifully, savagely embraces the interactive medium to force players to feel it for themselves.

NORCO begins sometime in the future, with a young woman named Kay Madère returning home to the titular community; her estranged mother, Catherine, has died of liver cancer, and it falls to Kay to organize the family’s affairs. Kay has been alone for a long time, having spent years wandering her dying country. In this future United States, the federal government is a distant and ineffectual non-entity; the southwest is in a permanent state of civil war; urban centers are either gentrified economic fortresses or crumbling asphalt labyrinths governed by militias and organized crime. Technology has advanced since our time—androids are common, and it’s now possible to digitize and upload parts of the human mind to a computer—but it hasn’t saved us.

With Catherine’s death, Kay’s only remaining family is her younger brother Blake. Soon after she arrives, he disappears without a trace; all signs indicate a connection to the mysterious “research” their mother had been conducting in the run-up to her death. Kay sets out to find her brother and, if possible, to figure out what Catherine was looking for—and why. Her efforts will bring her into conflict with several powerful organizations: the Shield Corporation, owned by the St. Claire family who run the local refinery; the Garretts, a cult of rootless young men led by the charismatic Kenner John; and a shadowy online network called Superduck, which sends unwitting users on errands in exchange for a strange new cryptocurrency.

As Kay, you’ll try to unravel the dual mysteries of your brother’s whereabouts and your mother’s research. After certain revelations the game flashes back to Catherine’s perspective; here you’ll control her on her own doomed quest for answers and learn where it took her as she tried to earn money she could leave to her children. You’ll control both women in first-person, with a slideshow presentation that hearkens back to titles like Shannara and Death Gate; gameplay is standard point-and-click, for the most part, with a few unique mechanics for different situations. (More on those later.)

Kay and Catherine each have a smartphone, which serves different purposes at various points; besides the world map and your character’s email, a handful of different apps figure into several puzzle chains. One of these—a voice recorder—leads to some of the best puzzles in the game, in which you’ll have to catch characters speaking on a given subject so you can play the clip for others. There’s also a memorable sequence where Catherine collects clues using an augmented reality program featuring a disturbing AI companion named “Friend.”

Though there is an inventory, it only figures into a handful of puzzles; information, not objects, is the game’s stock-in-trade. You’ll spend a lot of time with Kay’s “mind map,” which keeps track of who she’s met, where she’s gone, and what she’s learned. You access it by clicking her character portrait, which transports you to a dark cave in Kay’s mind. There you’ll see images of the people, places, and concepts she’s encountered. In practice it works like a classic detective’s bulletin board, with brightly colored strings joining disparate pictures in a web of unexpected connections. Whenever you learn something new that might be relevant to your objectives, the mind map will chime to let you know there’s a new connection available. The more you see and do, the more pictures and connections you’ll reveal; clicking the appropriate image lets Kay recap what she knows via dialogue, sometimes coming to new conclusions in the process. (The mind-map is exclusive to Kay; Catherine, who’s racing against her own mortality, keeps her focus on her immediate goal.)

You’ll generally work to solve your mysteries by talking to people and learning what they know. The bulk of the puzzles center on old-fashioned detective work: uncovering clues, following up with witnesses, and trying to piece things together, all while keeping an ear open for what they might let slip. These are a pleasure to solve, both in how they move the game forward and in the deeper understanding they provide of the game’s world. NORCO is an incredibly dialogue-heavy game, and listening and observing is the key to everything. How can you hope to know a place, after all, if you don’t understand its people?

To this end, great care has gone into developing the characters and their personalities. You’ll meet a plethora of memorable people in your travels: there’s the affably clueless detective, Brett LeBlanc, who lives out of his office and worries that everyone’s mad at him; there’s Dallas, the down-but-not-out family man who stays happy by listening to Christmas music year-round; there’s Lucky, the bayou-dwelling oil pirate who loves his dog and speaks in the third-person. There are no ciphers here; from central characters to bit players to the visually interchangeable Garretts, each character feels well-rounded and three-dimensional, as if they have an unseen life offscreen that will keep moving after you step away.

All of these people are very much a part of Norco, the community; they are shaped by it, as tied to its emotional and psychic landscapes as they are to the physical one. The past is all around them, lying in wait just below the skin of the present moment. Every object, location, and landmark you find will call up a memory for Kay or Catherine: a tough recollection from a childhood that ended too early; a fleeting moment of long-ago happiness; a painful memory of Blue, Catherine’s late husband, who was killed in a refinery explosion. An omniscient narrator describes, in poetic language, all the confused and contradictory feelings your current character experiences with each reminiscence. There are constant small moments where a seemingly innocuous observation reveals a hitherto-unseen dimension to Kay or her mother.

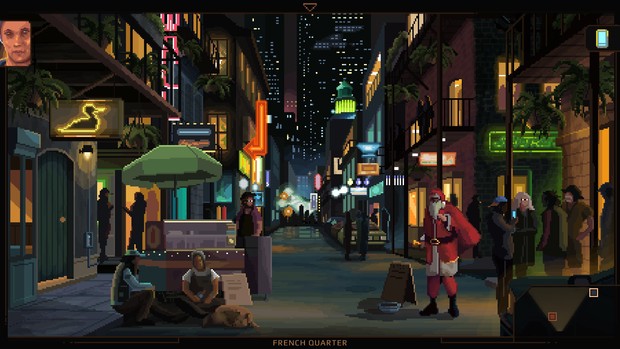

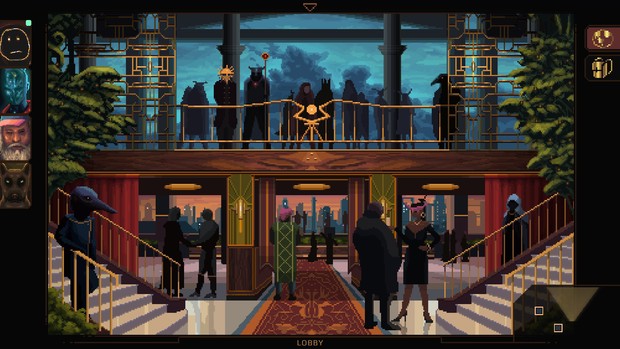

As moving as the writing is, NORCO often communicates most powerfully on the non-verbal level. Its pixel art landscapes are suffused with a palpable melancholy, its palette of dusky oranges and cool gray-blues evoking a perpetual sunset. The plaintive, wailing synth soundtrack by Louisiana artists Thou and Gewgawly I is shot through with a sense of loss and wounded longing for a world in decline. At times it feels like being in a dream in which you’ll understand something before figuring out what it is. (A lack of voice acting helps contribute to this atmosphere, though I’m not sure it was always part of the plan; it’s one of the few choices that feel budgetary rather than wholly creative.)

The imagery throughout the game is in keeping with this dreamlike quality. It’s often surreal—sometimes even menacing. Reality seems perpetually in flux, with the laws of existence as shifting and uncertain as Norco’s future, and its people’s. In a place standing on the border between life and death, it’s hard to be sure which world you’re seeing. The first-person perspective makes this more than a strange story; it’s a nightmare that you’re a part of, experiencing it and participating while also helping it to unfold. A touch of strange hangs about Kay herself: she and Blake are depicted without faces, with glum, glowing smileys standing in for their real features. Nobody ever mentions it.

Whenever you feel you’re getting a handle on the world, it throws a curveball at you: a vengeful alligator matron, for instance, or a pig-man patrolling the muddy passageways of time. There are monsters at work in Norco, make no mistake; some of them were human once. The world is bigger and more unusual than anyone understands; what starts as a straightforward story about returning home after years away ends roughly seven hours later as an epic about faith, consciousness, divinity, and our place in a larger universe.

Still, for a game that does so much so very well, it’s not without its rough patches. The worst of these are a pair of unconventional mechanics that seem intended to break up the gameplay into more diverse chunks; in practice, they just grind things to a halt. There are turn-based “combat” sequences sprinkled throughout that are neither necessary, interesting, nor in keeping with the rest of the experience; there’s some twitch-reflex clicking, some Simon-style memory matching, and then it’s over. No one speaks during the fight scenes, and when they’re finished nobody has much to say about them; they feel extraneous and unnecessary, like something from a different game. (There is, at least, a setting to turn them off, but I’d rather have had obstacles that felt like they belonged in the first place.)

The other questionable segments see you take to the bayou in a swamp boat, with the perspective switching from its usual first-person to an overhead map. These trips feature some of the game’s most interesting moments, as you navigate strange geography to uncover long-buried secrets beneath the surface, and the process should be flavored with ominous anticipation. Unfortunately, the finicky keyboard/mouse controls make getting where you need to go a slog, with slow turns, sudden jerks and plenty of narrow canals to bump and collide your way through. It robs the sequence of much of its power; if I’m searching a swamp for forgotten knowledge, I should be ready to engage fully once I’ve found it, not simply happy that I’m done looking. The boat controls slightly better with a gamepad, but movement remains sluggish and slow to respond.

Final Verdict

Everything else is best left to NORCO to reveal for itself; going on at length about it risks clumsily summing up what’s best discovered at the source. There’s so much on display that makes it easy to recommend, with an emotionally complex narrative full of memorable, well-crafted characters. It strikes a challenging balance between its fantastical elements and its deep grounding in the real world, and just about every element of its presentation is stunningly beautiful. Perhaps most intriguingly, however, what the game truly is defies description. I’ve seen frequent comparisons to other text-heavy games, most notably Kentucky Route Zero and Disco Elysium; such comparisons are not only off-base but miss the point. NORCO isn’t part of any trend, or subgenre, or design philosophy. It is, quite simply, exactly what it has to be to work as well as it does. At each turn, NORCO is authentically and emphatically itself, trusting the audience to find it in a place it’s carved out all its own, and to follow along where it leads. Those who do will surely find it haunting them long after they’ve finished.

Hot take

Simultaneously a work of baroque horror, a science-fictional condemnation of industrial capitalism, and a heartbroken elegy for a real-world place, NORCO is a captivating adventure game experience like no other.

Pros

- Authentic, one-of-a-kind narrative that keeps its roots in the real world while successfully blending science fiction and surrealist elements

- Pixel art beautifully brings the many characters and locales to life

- Excellent writing and characterization of both primary and secondary characters

- Synth score accentuates and elevates the game’s many moods

Cons

- Quick Time Event combat sequences slow the game down to little purpose

- Controls for swamp boat sequences are frustrating and detract from what should be powerful moments

- Lack of voice acting feels mildly jarring in a game with such vividly drawn characters

Will played his own copy of NORCO on PC.

1 Comment

Want to join the discussion? Leave a comment as guest, sign in or register in our forums.

Excellent review, adding to my wishlist pronto

Reply

Leave a comment