Makoto Wakaido’s Case Files Trilogy Deluxe review

- 0 Comments

Four, not three, standalone investigations detected in a clever Japanese side-scroller that favours style over gameplay substance

What differentiates, if anything, a game from a visual novel? Perhaps only overthinkers like me spend any time pondering such questions, and yet it may have a crucial relevance to the final word on Makoto Wakaido’s Case Files Trilogy Deluxe. While it presents itself with all the freedom of movement and interactivity expected of a game, this collection of four (yes, four, despite being marketed as a trilogy) bite-sized but engaging mysteries from developer Hakababunko is so undemanding that it may stray, for some, into visual novel territory. Boasting a stylish retro aesthetic and captivating twists, the stories play with perspective in fascinating ways, as well as with the information you gather—or that you think you gather—through working a case. For those content to witness such intrigue unfold from the distance offered by a novel, the Case Files are easy to recommend with little reservation. Those looking to wear out their figurative pipes and deerstalkers puzzling over clues will be delighted by a number of very smart subversions to investigative adventure tropes, but they’ll also likely find the experience as a whole to be full of unrealized potential. I am definitely in the second group.

As an anthology, the Case Files are comprised of unique standalone stories, all centered on the investigations of the detective Makoto Wakaido. Set in various vaguely defined locations in Japan (“K. city, H. prefecture,” “O. prefecture,” and so on), each begins in predictable, albeit grisly, fashion: with the discovery of a violent act. In “The Executioner Linchpin,” the victim has been decapitated and strung up to a telephone pole; a strange cult-like symbol is painted in blood nearby. In “The Bogeyman’s Woods,” the inhabitants of an isolated village insist that a poor soul murdered in the forest was spirited away by a vengeful deity, though the powerful but dysfunctional Sendo family arouses Wakaido’s suspicions. “The Phantom’s Foot” has a particularly bold premise, seeing the detective come to his senses, bloody knife in hand, watching as a wounded party dies right before his eyes with no memory of the events directly preceding the killing. Could he truly be the murderer, or is he himself the victim of an elaborate setup? “The Weeping Hand Manor” takes place within an old mansion that has been converted into a hotel. The manor attracts tourists eager to confirm local myths about supernatural phenomena. Initially arriving himself as a visitor, Wakaido is thrust into another investigation when a resident is injured during a power outage.

Each of the Case Files begins simply enough, but assumptions quickly unravel over the course of Wakaido’s investigations. As in most good detective fiction, there is never a shortage of suspects. For instance, in “The Bogeyman’s Woods,” virtually every member of the Sendo family has a motive, and various revelations about the interpersonal relationships between them—squabbles over inheritance, infidelities, etc.—complicate matters further. In “The Weeping Hand Manor,” past interactions between the attendants of the mansion—including ghost hunters and a youth club devoted to studying the paranormal—betray similarly complicated dynamics. Filling the shoes of the relentless investigator, you will be tasked with following trails of clues through conversation and observation. When Wakaido discovers a matchbook at the scene of one of the murders, for example, he traces it to a nearby bar, where he must find some way to appease an uncooperative barkeep into parting with valuable information about some shady characters who recently visited the establishment. In each story, an uncovered mystery leads to a deeper one, often revealing the situation as more complex—with more active parties—than was initially suspected.

A straightforward point-and-click affair, the interface is familiar but effective: You click on an open space to move, or on an object or character to interact, though you could also use the keyboard, which works just as well. The game is divided into discrete areas that can be explored. While you move freely within each, you travel from one scene to another by clicking a button to leave and then selecting a location on a map. Most settings are populated with at least one person, and all characters can be approached for conversation by clicking on them, which pulls up a few different dialogue options. Though moving through these selections will often generate new prompts, the original options usually remain present and can be revisited, repeating the same sequences of dialogue. In many scenes, certain objects are readily highlighted, indicating you can interact with them—this functions similarly to conversation. Wakaido carries a notebook expressed in the form of a menu that can be accessed via a button in the bottom right corner of the screen.

The notebook contains various pieces of evidence, presented as simple descriptions of objects, motives, and statements of fact—“bloody rake found in garden,” “Yoshiharu was seen at a local bar at the time of murder,” “Susumu’s mother resented him,” and so on. (These are hypothetical examples not found in the game.) Clicking on one shows an image of what person or object this clue is relevant to; leads you have already explored will show up as faded and marked with a check. You can click a button to select this piece of evidence, so that when you interact with the relevant character or object, a new prompt will be available to you. The game will let you know when you find a new lead, and there are around ten you need to find in each chapter before moving onto the next section. How many clues you have found—and the overall number you need to find—is almost always visible on-screen.

When you’ve found all the leads, you go to a place akin to a mind palace where a sequence of pillars stretches out before you. Approaching each one will prompt Wakaido to muse on the mystery, ultimately asking himself (and you) a question that must be answered by selecting the appropriate clue from the notebook. For example, he might observe (again, hypothetically) that Yoshiharu has been accused of murder but couldn’t himself have committed the act. Why not? You would then select the lead stating that Yoshiharu was seen at a local bar. Occasionally the questions require a bit more thought than that, but most of them do not. Sometimes multiple pieces of evidence could answer Wakaido’s question, which led me a time or two to select the wrong one. However, the game is immensely forgiving, and an incorrect response will simply prompt Wakaido to ask again.

While the finale of each story takes a shape unique unto itself, what they all share is that in some way they complicate or subvert the information you think you’ve been gathering. It would seem our investigator is always one step ahead of us, a fact he demonstrates by testing our detective skills in a final pop quiz. Unlike those asked at the end of chapters, these questions are actually rather challenging (though equally forgiving of wrong answers), success reliant on your ability to make seemingly minute observations the game doesn’t call attention to. I admit I did not do too well on these questions, but I found the approach utterly intriguing, and the times I was able to keep up with the detective were the most satisfying moments I had with the Case Files.

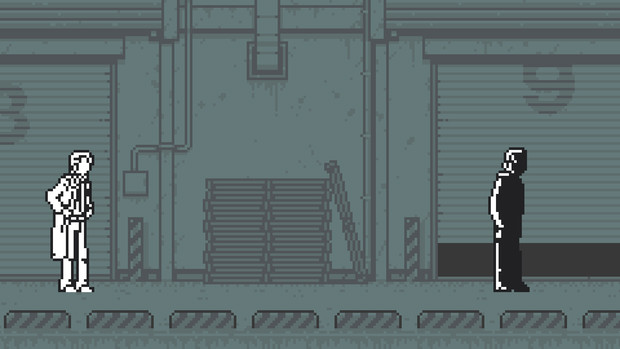

The art attracted me immediately and never ceased to impress throughout. Wakaido’s investigations take place within a striking environment, distinct yet evoking the vintage charm of both old pulp novels and 8-bit graphics. The character designs resemble a kind of inverted silhouette—distinctive traits (including most facial features) washed out in white, minimal markings filling in the necessary lines like crude sketches in black ink on white paper. Set against green-tinted monochromatic backgrounds, these figures contribute to an overall stark impression. Splashes of red blood stand out vividly, making the various murder scenes all the more impactful. Character animations are comparably simple but evocative, utilizing a precious few frames to create memorable gestures, such as the long drags the detective periodically takes on a cigarette. It’s captivating, and often strongly resonant.

The soundtrack is likewise effective at making use of the familiar. For the most part it’s comprised of moody but laid-back jazz pieces, trickling piano phrases and meandering upright bass lines conjuring the perfect atmosphere for a hard-boiled detective. When appropriate, the music takes a more particularized form—the eerie tunes of “The Weeping Hand Manor” are a great example, exhibiting a strong command of horror. The score to “The Bogeyman’s Woods” is my favorite, particularly a haunting composition of winding, multilayered woodwinds that plays as Wakaido chases the mystery through the dark, dense forest. The music is performed with virtual rather than live instruments, which befits the vintage feel of the game. The sound design is further fleshed out with miscellaneous touches and effects when required—howling wind and pouring rain, footsteps, a brief piano motif that signals the discovery of a clue. Consistent with the indie retro vibe, there is no voice acting.

The Case Files are as compelling thematically as they are aesthetically. Pursuing mysteries that grow ever deeper is something foundational to the detective genre. The way in which these stories explore questions of perspective makes them special, however, especially in an interactive context. It’s one thing to undergo an elaborate investigation where perplexity builds upon perplexity, but yet another layer is added when the process calls into question identity and sense of purpose. To expound on this would spoil the fun, but suffice it to say that the concluding chapters to each of these mysteries—the way they recontextualize aspects of the investigation—make for worthwhile and indelible experiences.

And yet the benefits of keeping players in the dark more than necessary might, for some, be perceived as a weakness. For all the style, charm, and resonance at work here, there is a certain distance between player and character that keeps things at an arm’s length. It isn’t just that Wakaido has access to information you don’t, it’s that the process of collecting clues is so easy that it becomes rote and impersonal. I often felt I wasn’t investigating at all, I was simply progressing through an experience crafted for me beforehand, inputting the relevant commands so that I could watch a master detective do all the work. There is one sequence in which the avatars in the notebook that essentially spoon-feed you answers are removed for plot-driven reasons. This felt much more compelling to me, but as fascinating as it was, its brevity—as well as the fact that it only happens once—just reinforced the impression of great unrealized potential throughout the Case Files.

Restricting the avatar hint system to an easy mode might have helped; another approach could have been to make the more challenging questions at the conclusions consequential. But as straightforward as I found the gameplay to be, one of the stories has another hint system that streamlines the collection of information to an even greater extent, directly telling players what object or character to approach and what prompt to select to advance. This makes me wonder if the Case Files were intended to be played differently than I approached them. The developer claims that these stories can be completed in under an hour, but each of them took me at least two to three hours to play through. Could this be less a description than a challenge? Perhaps it’s not whether you can make the necessary deductions, but the efficiency with which you do so. It’s an interesting idea, though entirely speculative on my part, and I imagine most gamers will similarly take more joy in pursuing all possible leads as thoroughly as possible before arriving at a conclusion.

Final Verdict

Makoto Wakaido’s Case Files is a solid collection of brief but entertaining mysteries that offers an illuminating take on the mind of the investigator. It mines the best of the past in its presentation, bringing the world to life with expressive art and music. With its likeable lead and sly twists, it is sure to scratch the itch of detective fiction enthusiasts who aren’t necessarily looking to torture themselves to arrive at difficult deductions. While the rare moments in which it does provide a challenge or otherwise disrupt the typical casual mode of its gameplay left me wishing for more, I nevertheless commend the creativity and cleverness throughout. In the end, Detective Wakaido’s sleuthing efforts add up to a bold, stylish treat, and a welcome if not particularly interactive addition to the world of investigative adventure.

Hot take

Light on gameplay but rich in atmosphere, the short but sweet stories that make up Makoto Wakaido’s Case Files are full of entertaining misdirection and unique subversion of perspective.

Pros

- Charming, distinctive art and music

- Smart deviations to the detective game formula

- Compelling exploration of perspective

- Engaging twists and turns

Cons

- Little to no challenge or consequence for failure

- A sense of distance between player and protagonist

Andy played Makoto Wakaido’s Case Files Trilogy Deluxe on PC using a review code provided by the game's publisher.

0 Comments

Want to join the discussion? Leave a comment as guest, sign in or register in our forums.

Leave a comment